This year, I graduated from a Master’s program. Finishing graduate school was one of the hardest things I have ever done. I had spent the last three years reading, writing, grading, crying, self-doubting, and regretting the decision to enroll in the first place. But I had finished. I had earned my credits and written and defended my thesis. I had not only finished, but excelled. I did my work and I did it well.

But after I completed my walk across the stage, empty diploma in hand, I thought, “What now?” When I spoke to my friends and relatives and received their congratulations, they asked, “What now?” My responses were always the same: “I don’t know” or “I’m not sure.”

But really, I knew exactly what I wanted: rest. I wanted to be in my soft girl era.

Soft Girl Era

Urban Dictionary defines the “soft girl era” as one “in which a female chooses to only have kind, loving, gentle and supportive people in her life. It is a time where she makes an effort to live in peace, happiness, and calmness.” I did not want to just take a short break for a few weeks or months while I figured out my “what now” and prepared to make my “next move.” I did not want temporary periods of rest in between bouts of hustle. I wanted a life of rest and softness–consistently and unapologetically. I wanted to be in charge of my day to day life, to be able to hold onto what contributes to my own happiness and peace, and simply eliminate what doesn’t.

A soft girl may have a 9 to 5 job that she adores, but she sets boundaries to create work / life balance and prioritize her own interests. A soft girl may also stop working to have brunch at 11:00 am on a Wednesday if she chooses to. A soft girl is gentle with herself, puts herself first, and does not apologize for doing so. A soft girl’s life can look any way she wants, because it is hers by design.

I just wanted my “what now” to be soft. But I never said it, because I never felt like it was an acceptable option for my “what now.” It wasn’t what anyone wanted or expected to hear. My parents probably wanted me to say that I was going to law school and my grandparents wanted me to say that I was going for a PhD. I answered, “Maybe” or “We’ll see.”

In the midst of all the questions and opinions from other people, I often think about my Masters thesis. I think about all the research I had done, the books I read, the new ideas I had discovered and explored–my own and those of others. The project is called “Black Girl Magic: History, Identity, and Spirituality in Contemporary Fantasy and Science-Fiction.” In the novels I chose for my project, the protagonists were Black women who performed literal acts of magic–looking into the future, communicating with spirits, and controlling the elements. With magic, they are able to manipulate the world around them, creating change, and designing a world in which they not only can survive, but one in which they thrive.

Black Girl Magic

The phrase “Black Girl Magic” was coined by CaShawn Thompson in 2013 as a social media hashtag that acknowledges the outstanding successes and everyday existence of Black women and girls. It is a reminder of the beauty and resilience of Black womanhood. It demonstrates an immeasurable sense of strength to move through a society that was designed to make us weak, that pushes us to the bottom of society and tries to make us believe we belong there. But using Black Girl Magic as a mindset, Black women and girls–along with all women of color and other minority or underrepresented communities–know that we deserve more, as stated by Valerie McPherson in Refinery29. McPherson writes, “[The soft girl era] allows me to express my emotions, romanticize my life, and get in touch with that gentle side of myself that can become entangled with the problems around me. As a brown-skinned Latina, I deserve this. More than that, embracing my inner soft girl shows others like me that they deserve to, too.”

We do not deserve to have to struggle and be strong all the time. We deserve more. We deserve peace, rest, and love. We deserve to be treated gently by others and by ourselves. We deserve to have soft lives. And we, as Black women, have always known that we deserve more.

Black women and other women of color today who embrace the concept of living soft lives and embody the “soft girl” aesthetic are drawing from a long history of like minded women who prioritized their own rest and healing in a world that doesn’t automatically award them the space to do so.

Examples

- Black women demanded soft and gentle lives as early as the 19th century. In 1851, Sojourner Truth delivered a famous essay entitled “Ain’t I a Woman?” in which she insisted her physical and mental strength were equal to or greater than that of any other man, white or Black.

- These sentiments escalated even further throughout the 20th century. In 1977, the Combahee River Collective demanded, “Black women are inherently valuable, that our liberation is a necessity… because of our need as human persons for autonomy.”

- In the preface to The Black Woman: An Anthology* (1970), Toni Cade Bambara writes, “What characterizes the current movement of the 60’s is a turning away from the larger society and a turning toward each other. Our art, protest, dialogue no longer spring from the impulse to entertain, or to indulge or enlighten the conscience of the enemy… Our energies now seem to be invested in and are in turn derived from a determination to touch and to unify. What typifies the current spirit is an embrace” (1).

- Bambara’s novel, The Salt Eaters* (1980) focuses on the connection between wellness and spirituality and the importance of community and connection in healing the individual self. Minnie Ransom, a Black woman healer, “could dance [her patients’] dance and match their beat and echo their pitch and know their frequency as if her own… [S]he knew each way of being in the world and could welcome them home again, open to wholeness… [S]he would welcome them healed into her arms” (48).

- With a title that pays homage to Bambara’s acclaimed novel, bell hooks published Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery* in (1993). Hooks declares, “Black female self-recovery… is an expression of a liberatory political practice. Living as we do in a white-supremacist capitalist patriarchal context that can best exploit us when we lack a firm grounding in self and identity (knowledge of who we are and where we have come from), choosing “wellness” is an act of political resistance” (7).

These women and their contemporaries were gentle with themselves in a world that is often less than gentle toward them, because they deserved it. And their work laid the foundation for me, for all of us, to do the same. All of these texts were included in my Master’s thesis on Black Girl Magic. And though I didn’t know it, because of these authors, I already had everything I needed to choose myself and define my “what now.”

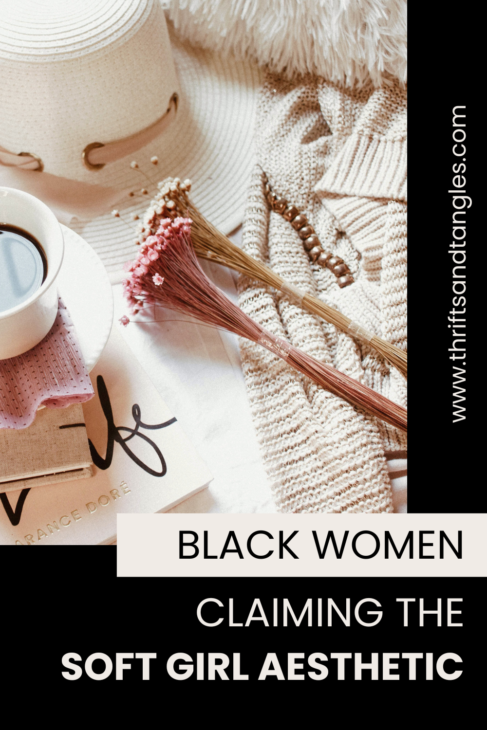

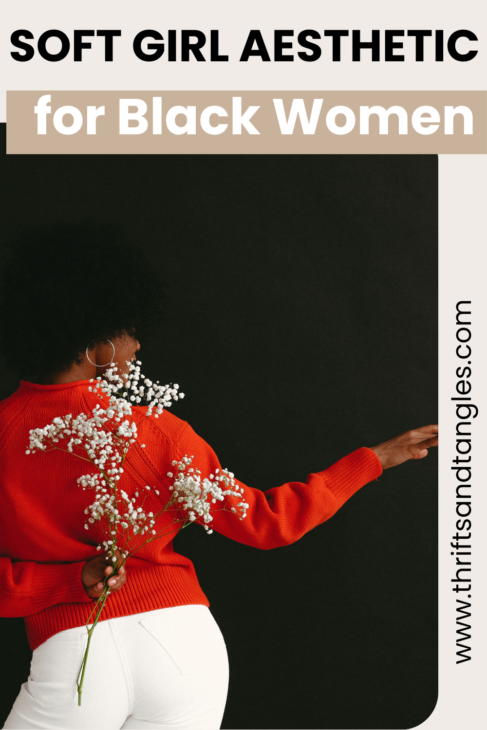

Pin it for later!

Girl! So so good! A read I didn’t know I needed but I’ve been feeling every bit of this “soft girl era” emerging inside of me as well.

Prior to reading this article, I did not understand the “soft girl era,” term. This truly simplified everything and made me feel there are women in this world who share the same feelings as myself. This made me feel really good and I am happy to have come across your blog. 💕

This was very uplifting. I, myself, am striving to achieve this now. Thanks for sharing.