I have very vivid memories of hating my natural hair and its curly, kinky natural texture. This hatred first emerged when I was very young and persisted through my teenage years into adulthood. I thought it was too frizzy, too tangled, too unmanageable, always too short. And too unlike that of my white friends and classmates. As I grew up and into myself, I became more comfortable with my hair. I stopped straightening it several years ago, opting to wear it natural or in braids or twists. But to this day, those old, ugly feelings of inadequacy and unattractiveness still find their way back in. At 24 years old, I become a little girl again who hates her hair, refuses to believe she is beautiful and wishes for something she will never have.

Why do those feelings reemerge after all this time? Why now, when I am an adult and no longer a child, and when natural hair is more popular than ever? The evolution of Black natural hair is heavily and undeniably influenced by enslavement and colonization. These two systems perpetuate and rely on a series of social and political processes to dehumanize, oppress, and police Black people. One of these processes taught Black people to hate our natural hair. Now I know the history behind these thoughts and now I understand what (and who) put them there. Throughout history, when Black hair is used as a weapon for oppression, Black people use it as a weapon of resistance.

Colonial Intrusion & Forced Enslavement

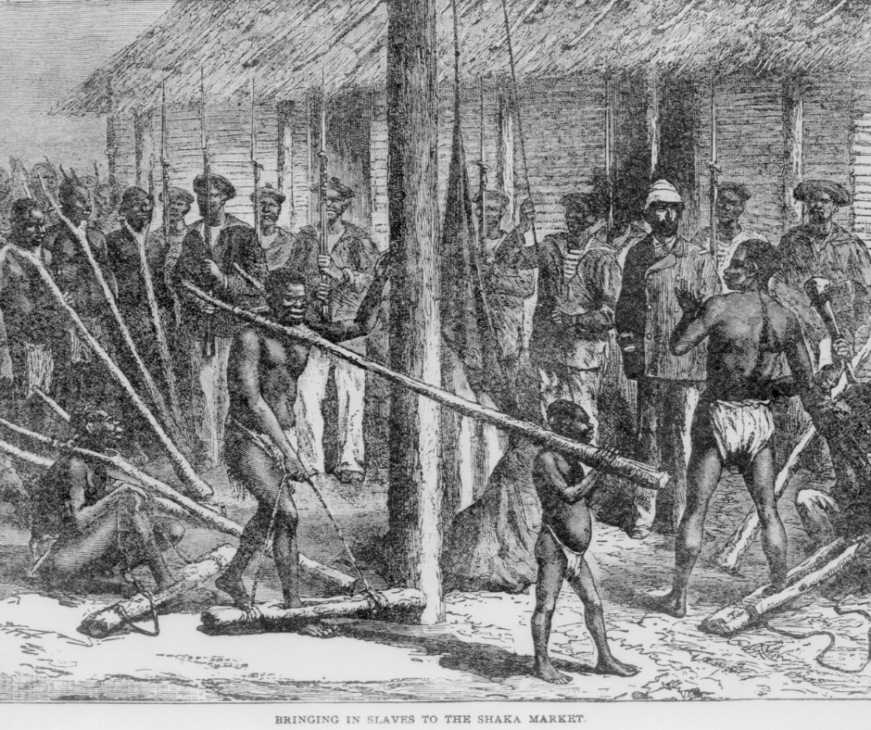

Traditionally, in West African cultures, hairstyles were used to signify individuals’ age, occupation, rank, religion, marital status, family group, or ethnic group. And the processes of hairdressing and hair care were often a collaborative, communal process that brought people together and strengthened familial or ethnic ties. Proverbs from the Yoruba and Mende ethnic groups in modern-day Nigeria and Sierra Leone describe hair as a “Black crown,” associate it with “abundance” and “plenty” and describe it as “long and thick.” Note the sharp contrast between this and my own childhood descriptions—unattractive, unmanageable. The only things standing between these traditional proverbs and my modern insecurity are colonialism and enslavement. We can trace the stigma surrounding Black hair directly to the presence of European colonizers, who described Afro-textured hair as “nappy,” “wooly” or “matted,” comparing Black hair—and Black people—to animals. The dehumanization of the Black body is what justified and perpetuated slavery in the United States.

Just like on the continent, hairstyling served as an identifier for enslaved Africans in the United States. When they arrived on U.S. soil, enslavers often forced Africans to cut or shave their hair, supposedly because of sanitation concerns. But in reality, it stripped the Africans of their relationship with their hair, which was a significant part of their identities. As a result, these different ethnic groups—including Ashanti, Ibo, Yoruba—arrived on U.S. soil anonymously and stripping away individual identities helped to justify the institution of slavery.

How We Resisted:

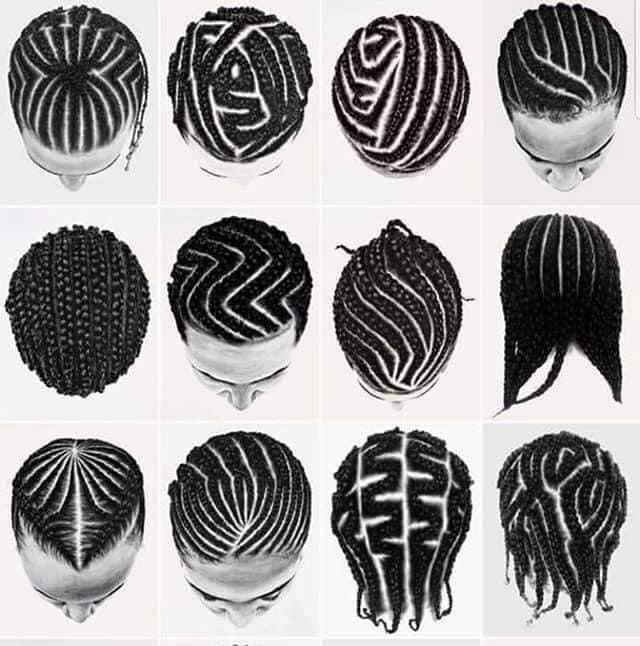

Most enslaved Africans came from Central West Africa, including modern-day Ghana, Nigeria, Benin, Sierra Leone, Senegal, Gambia, and Cameroon. Although white slavers stripped Africans of their hair, the traditions and customs associated with it lived on. Enslaved Black people started braiding their hair again to reconnect to their African roots. Braiding patterns were often specific to various regions and ethnic groups used to identify and differentiate between communities.

Africans and Black Americans also used hairstyling as a survival tactic. Anticipating that they may face capture and forced enslavement, Africans smuggled supplies—rice, seeds, sometimes even gold—onto slave ships to help sustain the voyage across the Atlantic and increase their chances of survival in the New World. How? By braiding them into the scalp, hidden from their captors. Similarly, there is evidence that during enslavement, Black people created intricate braiding patterns to exchange messages and map their routes to freedom when they were planning to escape. Despite the efforts of enslavement and colonization to dehumanize and devalue it, this so-called “wooly” and “matted” hair in many ways helped the enslaved to survive.

Coartación, the Tignon Laws & a Shifting Social Order

In 1786, Governor Esteban Rodriguez Miró passed the Tignon Laws in Louisiana, which prohibited Black women from showing their hair in public and forced them to cover it with a headscarf. For context, at the time, Louisiana was a Spanish territory, and in 1769, the Spanish passed the law of coartación, under which enslaved people could purchase their freedom. Most of the enslaved didn’t benefit at all from this law. However, there were a handful of Black people who were able to purchase their freedom, and once free, they began to disrupt the social order in Louisiana by building wealth and rising in status.

As free Black women entered society, they began to dress in finer and more elegant clothing, showing off their femininity and attracting the attention of white men, even further disrupting the social order between Black and white people. Enter the Tignon Laws, intended to police Black women’s appearances, eliminate the small amount of empowerment they had found, and force them back into subordination and inferiority to re-establish the social order.

How We Resisted:

However, these laws allowed Black women to use hair and dress as a form of resistance, once again. Think back to how they used ancestral African braiding styles to resist enslavement and maintain a sense of community. After the Tignon Laws were passed, instead of succumbing to the oppression, Black women showed out, wearing colorful, decorative tignons and wrapping them in intricate patterns, again drawing from African traditions. They reclaimed the tignon as a symbol of pride and beauty that transferred into modernity, as headwraps become a popular accessory for Black women today.

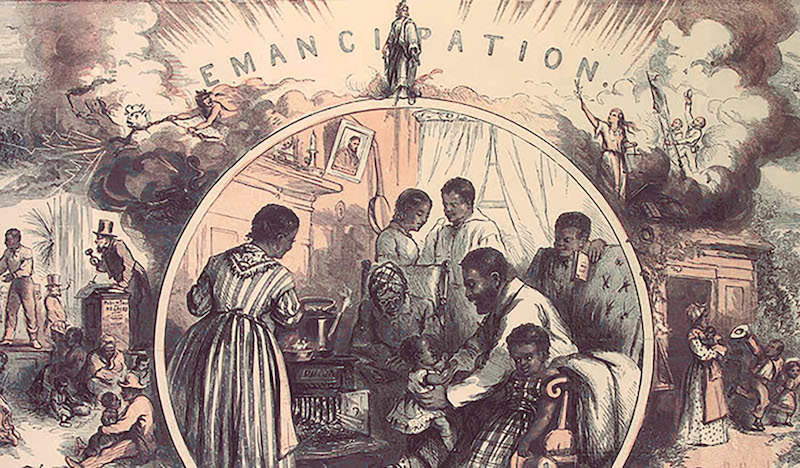

Emancipation, Reconstruction & “Good” Hair

The Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863, declaring “freedom” for enslaved people. (For context as to why this deserves quotation marks, see here and here.) In the decades after the Civil War—called the Reconstruction Era—newly freed Black people sought opportunities for economic and social growth—along with basic survival—the key to which was assimilation to whiteness.

During this era, society welcomed the idea of “good hair,” referring to hair that more closely resembles straighter textures. In other words, “good hair” was not Black hair. Black people—men included—hair textures were viewed as better adjusted and more successful and often held an elevated social status because they were essentially closer to whiteness and more removed from Blackness. In 1905, Garrett Morgan invented the first chemical hair-straightening solution. The product was marketed with promises of beauty, opportunity, status, and racial uplift in exchange for their own shameful, stigmatized Black hair, a problem that needed to be tamed and managed. Morgan’s product was the first of many and the next few decades saw an extraordinary market increase for Black hair products—relaxers, pressing combs, wigs, hairpieces.

How We Resisted:

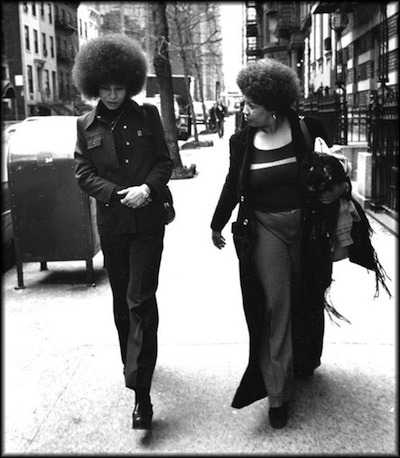

The “Black is Beautiful” movement first emerged in the 1960s and became the first wave of the natural hair movement. For the first time, Black hair was not just a problem. It was not a symbol of shame, but one of beauty and power. As they pushed for civil rights, Black people wore Afros (called “naturals”) to express Black pride, Black power, and resist oppression and Eurocentric standards of beauty. Just like the 18th-century Black women who reclaimed their tignons for their own power.

The push for Black power and the celebration of Black beauty continued throughout the remainder of the 20th and into the 21st century:

- Afros in the 1970s as a fashion choice instead of just a political statement.

- Locks/Locs (rooted in ancient Egyptian cultures) and Jheri Curls in the 1980s.

- Braided styles, always essential to Black and African culture, but popularized in the mainstream. (See Janet Jackson in Poetic Justice.)

- The second wave of the natural hair movement in the 2000s, thanks to an emerging community of Black content creators, especially on YouTube.

When I was little I used to dread wash day. I would cry and fidget and scream the entire time. I was learning, unconsciously, to associate my natural hair with pain. I felt physical pain when my mom pulled the comb through the tangles and got too close to my ears with the hot comb. I felt emotional pain when I began to notice the differences between me and my white friends at school. I was sure they didn’t have to go through all of this distress to make their hair look “presentable”. My mom taught me to toughen up through the tangles. My dad would come to my rescue, wiping my tears and telling me, “You’re gonna look so pretty when your hair is done” to make me feel better. And it did. But my natural hair has always been something I had to endure, a problem I had to be strong enough to deal with. A literal representation of “beauty is pain.” Black women and girls are taught to compare ourselves to other people’s definitions of beauty, and then to push through them. But what we eventually have to learn as we get older is not only how to push through, but also push back.

\

Similar Posts

- All My Friends are Natural

- Life by MJ’s Natural Hair Journey

- 50+ Resources to Educate Yourself About Anti-Racism and Race

Sources

https://www.nps.gov/ethnography/aah/aaheritage/histcontextsd.htm

https://www.amplifyafrica.org/post/tignon-law-policing-black-women-s-hair-in-the-18th-century

https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/the-history-of-louisiana-tignon-laws

https://case.edu/ech/articles/m/morgan-garrett

https://daily.jstor.org/how-natural-black-hair-at-work-became-a-civil-rights-issue/

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3337689?origin=JSTOR-pdf